The Pads and Reeds (Tynes)

Notes on the Pianet T are produced by the key lifting a small silicone pad. This pad sticks to the reed by a process known as polymer attraction, and at some point the bond breaks, allowing the reed to spring back. This design was apparently patented by NASA.

There are different types of polymer attraction but, in the Pianet, the mechanism relies on the use of a non-evaporating oil which coats the surface of both the reed and the pad and makes them ‘sticky’. You could consider it to be a form of suction, like pulling a rubber sucker off a window. It doesn’t really work like that, but the analogy might be useful.

For this to be effective, both surfaces need to be smooth because the very thin film of oil has to form a seal, otherwise it doesn’t work. The film has to break up evenly and ‘fail’ in one smooth snap. If you have roughness it generates pockets which cause the film to separate unevenly, and the pad doesn’t ‘pluck’ the reed with the maximum force.

Pads

When you look at the top and sides of the silicone pads, they are exceptionally shiny whereas the bottom surface is ever-so-slightly matt, where it has been in long term contact with a slowly-corroding reed. Whether this will be a significant problem remains to be seen. If it is, there may be ways to restore the surface, but until we get further along with the restoration we won’t know. The tops of some of them have thin flaky edges which look like flash from a moulding process, so they may be heat-moulded, in which case it might be possible to make something to melt the bottom of the pad and restore the original mirror finish. Alternatively, we may be able to either slice a tenth of a millimetre off the bottom of the pad to reveal a new surface by making a jig similar to a microtome, or to cut a section off the bottom of the pad and stick it back on upside down. Some way will be found.

Reeds

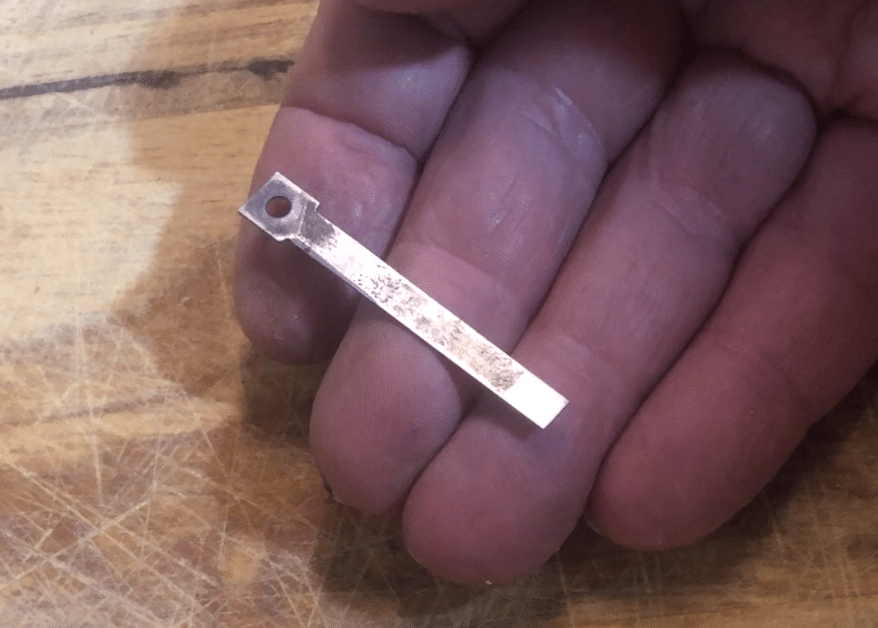

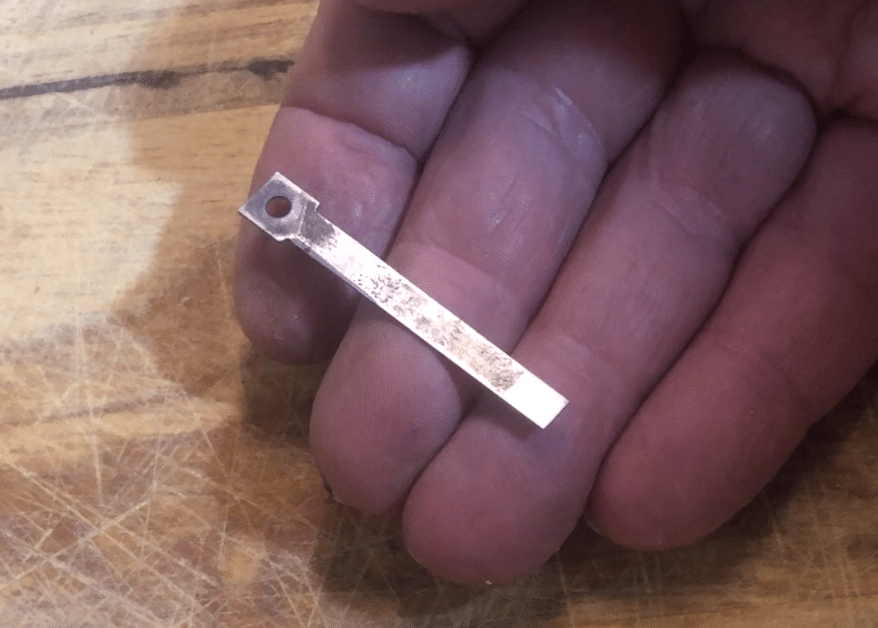

As we saw in Part 1, the reeds are corroded, mostly on the top surface where the most condensation probably formed.

Looking online at the comments made by others who have restored these instruments reveals a lot of information, and much of it is conflicting. Some say not to clean the rust off the reeds. Some say never to use anything abrasive on them because it will only make them worse. Some have had success polishing them up. Some say to clean them only with Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA). Some say never put any oil on any of the surfaces – although the method employed to ‘pluck’ the reeds using polymer attraction relies on a thin film of oil. Some go as far as to say that an instrument with rusty reeds can never be made to work properly.

These reeds are almost certainly steel and are ‘blued’. On most reeds, the surface below the pads is reasonably intact.

Oxidised corrosion will add mass to the reeds. Iron becomes heavier as it rusts, which you’ll see if you burn steel wool, because Iron Oxide is formed from the addition of oxygen. This rust will therefore make the reeds tend towards a lower pitch. If we clean it off we’ll finish up losing material, which will upset the tuning in the other direction. I also have concerns about a corrosion layer in terms of the resonance, which is one of the features of this instrument.

The reeds are coated with a layer of bluing lacquer. It’s not heat treated, definitely a lacquer because it scrapes off. Although the area under the pads is often reasonably intact, I don’t think that ‘reasonably intact’ is going to work.

Plan

My first plan is to try refurbishing that reed which I first removed in Part 1. You may ask why I don’t choose one at the end of the keyboard, where it’ less likely to matter, but quite frankly it doesn’t matter. It’s not as if any of the keys work well enough to make the instrument usable and we could get away with leaving them alone. If we can’t fix this the whole Pianet is only good for parts, so it makes little difference where we start.

In terms of a plan, there are many things to consider:

- We could turn the Iron Oxide to Iron Phosphate using phosphoric acid, which would prevent further corrosion. It still adds mass to the reed and does nothing for the surface, which I am concerned about from a resonance point of view. It does nothing for the overall finish of the area that comes into contact with the pad.

- We could clean off the rust completely, which will reduce the mass of the reed but will not provide any protection, nor will it help with any surface imperfections.

- We could do one of the above and then polish the surface. Although others have said never to use anything abrasive on the surface (and polishing is abrasion) one may assume in the absence of any clarification they mean: “Don’t use grit paper on it”. At least the area under the pad needs to be smooth, so there’s little option but to do something with the surface, i.e. polish it.

- Unless care is taken, polishing will create a convex surface because anything soft will tend to polish the edges more than the middle. If we polish, it needs to be by rubbing the entire flat surface on something hard, like a stone or a diamond polishing pad.

- Since various areas of the original bluing lacquer are damaged I feel this is also likely to affect the resonance. As we have seen when we looked at a reed in Part 1, the original tuning process involved grinding off material through the lacquer, however most of the surface remained intact. It is unclear what purpose that lacquer serves as the areas of metal exposed by tuning have not corroded noticeably.

- Whatever we do must provide some continued resistance to corrosion.

In short, a whole range of different opinions from others, many borne out of experience I’m sure, but at the same time still conflicting, coupled with a list of requirements which seem not to be totally achieved by any of the solutions put forward by others.

My plan is to make the best attempt I can to restore the reeds to a condition that allows them to operate most effectively, and as close to the original state as possible. It will not be perfect, because a balance will have to be struck between surface finish (resonance), corrosion resistance, and the performance of the ‘pad plucking’ mechanism, but the aim is to return the instrument to a rich-sounding state, which stays in tune.

My first thoughts are as follows:

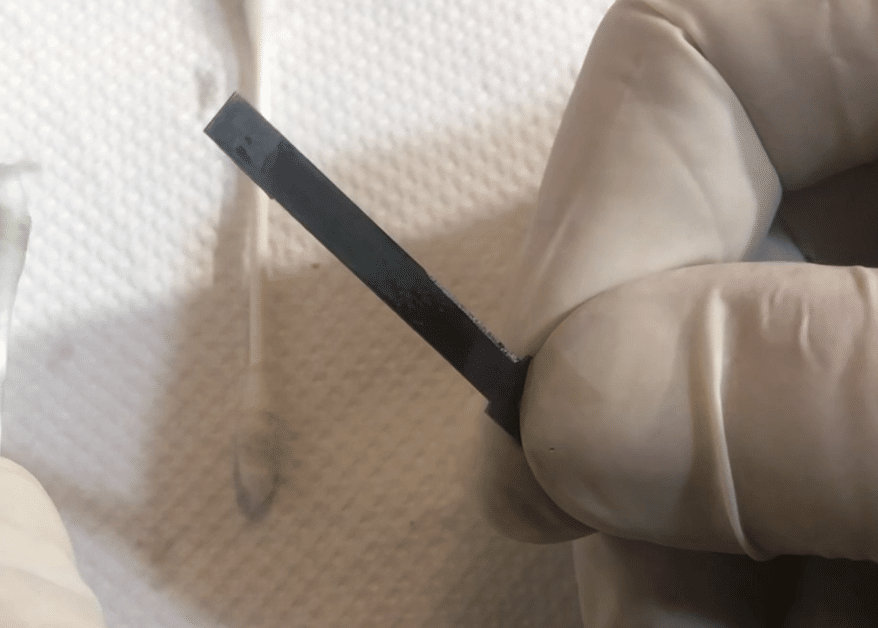

- Treat the surface with Phosphoric Acid to convert any Iron Oxide to Iron Phosphate.

- Remove the original blue lacquer finish, together with all surface roughness, which is the Iron Phosphate.

- This will leave any tiny pits in the surface filled with Iron Phosphate, resulting in a uniform smooth finish.

- When Iron Oxide is converted to Phosphate it swells slightly, which is why I wanted to do that first

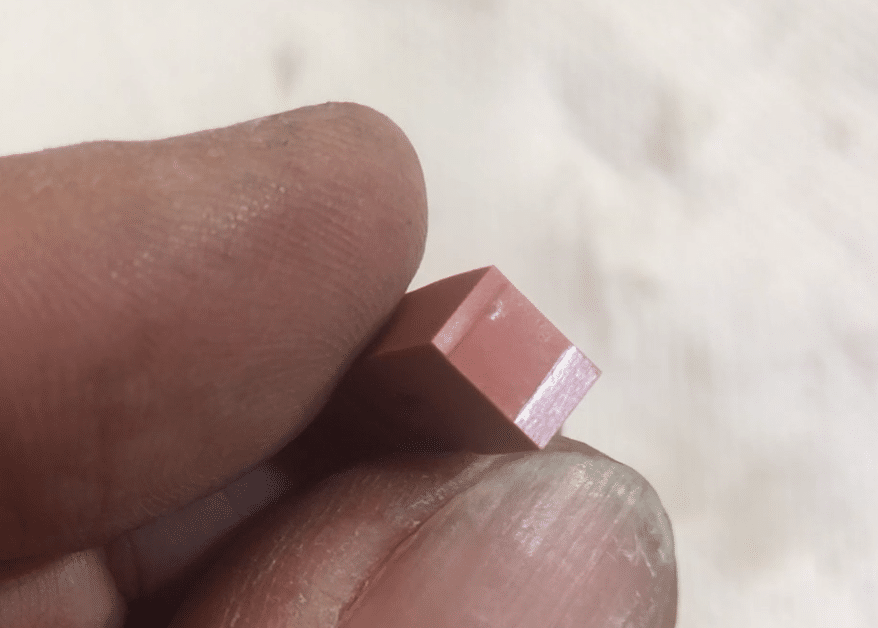

- I will then blue the surface using a chemical-based bluing method to add a corrosion-resistant layer

- Chemical bluing does not affect the material structure in the way that heat-treatment would

- The chemical used should not affect any Iron Phosphate that remains in surface pits

This blued surface is caused by a surface reaction, and is not an additional layer of coating. Hopefully, this will result in the reeds now being tuned over pitch, meaning that they can be corrected by adding small amounts of lacquer to the end of the reed, rather than having to remove material.

Bluing, in itself, does not make a surface highly resistant to corrosion. It is customary to add a layer of oil. We do not want to make the surface sticky, which would attract dust, and neither do we want to introduce a layer of oil, some components of which will evaporate over time, as both these things will adversely affect the tuning of the reed. However, the PDMS oil which is used to engineer the ‘plucking’ mechanism is specifically non-evaporating, so an extremely thin film of that which can be applied to the reed simply by handling it should help to provide additional resistance while not being sticky enough to capture significant dust.

This is why I’ve been eagerly awaiting the arrival of the postman.

Refurbishing A Reed

The intention of this process was to remove as much surface rust as possible, convert any remaining in surface pits to an unreactive compound that will not promote further oxidation, and add a protective layer which replaces the original blue lacquer. This, I feel, will help to restore the tonal quality of the reed.

We took some measurements of pitch and signal amplitude before the reed was removed, and the next step (in Part 3) is to reassemble that key mechanism and repeat those measurements. Hopefully we will find an improvement. If not we will need to think again.

Additional Notes and References

Chemical Reaction Of Phosphoric Acid

This is a conversion reaction which converts Iron Oxide (rust) and Phosphoric Acid to Iron (III) Phosphate and water. In these chemical names, the suffixes (I,II,III) refer to the oxidation states.

Fe₂O₃ + 2H₃PO₄ -> 2FePO₄ + 3H₂O

Iron is a reactive metal, which is why it combines with Oxygen so easily to form Iron Oxide. It forms triple-negative ions (Fe-3)

In the configuration with Oxygen which forms double-positive ions (O+2) it has to share bonds with two Oxygen atoms, which is why it finishes up as Fe₂O₃

O=Fe-O-Fe=O

The Phosphate group in Phosphoric Acid already has a triple-positive configuration (it’s PO₄-3) so Iron would rather bond with that, and has no problem ripping the Hydrogen off it. This Iron Phosphate (or Ferric Phosphate as it is sometimes known) is black in colour, and doesn’t bind to the Iron lattice very well, which is why you can see some dark smudges on the photograph. That just shows that we are still removing some rust, which is fine.

Chemical Bluing

The bluing process I have used involves a reaction between Atomic Iron, Selenous Acid, and Copper Sulphate to deposit a coating of Copper Selenide. Other chemical process are sometimes used which generate a type of black Iron Oxide, which is not the typical one we think of as rust. There are an lots of different Iron Oxides.

This is really a multi-stage process, but it is common for the required mixture of reagents to be applied together as they do not react with each other. We have already primed our piece by converting the majority of the rust to Iron Phosphate, but some chemical bluing solutions may contain Phosphoric Acid which would further clean the surface as part of the reaction.

The first step involves creating Copper atoms, and the typical way to do this is to enable a displacement reaction between the Iron lattice and Copper Sulphate. This is sometimes called an oxidisation-reduction reaction.

As you might recall from high school chemistry, Iron is more reactive than Copper, so it replaces the Copper atoms in the Copper Sulphate, producing Iron Sulphate, and free Copper atoms.

Fe + CuSO₄ → FeSO₄ + Cu

This would typically ‘plate’ the iron with a copper film, if we did not almost immediately convert it to Copper (II) Selenide (CuSe) by reacting it with Selenious Acid (H2SeO3).

A lot of confusion is likely to arise if you start looking these reactions up in books or online. Just as Iron can form many types of Iron Oxide, Copper can form various different types of Selenide.Other bluing techniques involve heating the metal and plunging it into various liquids, notably oil. These generally give a better and more resilient surface because the process alters the metal by introducing carbon into the surface layers in a similar way that case hardening does. The heating would also modify the crystal structure of the steel and affect the tonal qualities of the reed in a way which adding a very thin cosmetic layer will not. We therefore can’t consider that as an option.